Unbeatable tic-tac-toe with Pygame - pt. 1

Overview

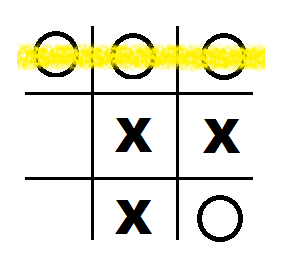

Tic-tac-toe is a game for 2 players, X and O, who take turns selecting positions on a 3x3 board. To win, one player must manage to place three of their marks in a row, either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

In this example, player O has won, as they have marked 3 of their symbols along the top row.

In this example, player O has won, as they have marked 3 of their symbols along the top row.

Goals

In this post, I’ll program an AI with the logic for playing a perfect game, so the user playing against the computer can do no better than draw.

I’ve also built two UIs - a command line UI to play against this AI, and a UI leveraging the pygame package.

Base game

The game itself is relatively straightforward, as a single game only needs to maintain the board, remember what selections have been made by which user, and accept input from either player to update the board.

I’ll use a numpy array to hold the 3x3 board, using a 0 to denote the location has yet to be marked, 1 to denote that player X has marked the location, and -1 to denote that player O has selected it.

class TicTacToe():

def __init__(self):

self.board = np.zeros((3,3), dtype=np.int8)

self.game_finished = False

self.user = 1

In my implementation, player X (denoted by 1 in the board array) will be the user, always going first, and player O (denoted by -1 in the board array) will be the computer.

Game loop

Starting with player X (denoted by 1 in the board array), each player will get a turn to make their selection, updating the board.

class TicTacToe():

def run_game(self):

while not self.game_finished:

if self.user==1:

# user has made fewer moves, so let them make the move

move = self.get_users_move()

self.board[move//3, move%3] = 1

else:

# make computer move

self.make_computer_move()

# check if the new move made either player win

self.game_finished = self.is_game_finished()

self.user *= -1

...

After each player chooses a location, we’ll check if the game should end. If not, the next player gets their turn.

Getting user input

User O (denoted by -1) will make moves programatically, and this method will be discussed later in this post. User X (denoted by 1) will be played by the user, and so needs user input.

CLI

In the command line version, the user will be presented with the current layout, and asked to enter an integer, 0-9, to denote their move of choice, starting with 0 in the top left, and working left to right, top to bottom:

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 |

If the user enters a location that has already been selected, they will be prompted to choose again.

class TicTacToe():

def get_users_move(self):

# display the current layout

print(self.board)

while True:

# get user input and update board accordingly

try:

move = int(input("Enter your choice (0-9): "))

assert self.board[move//3, move%3]==0

return move

except:

print("Enter valid input (0-9) that has not already been selected.")

continue

Pygame

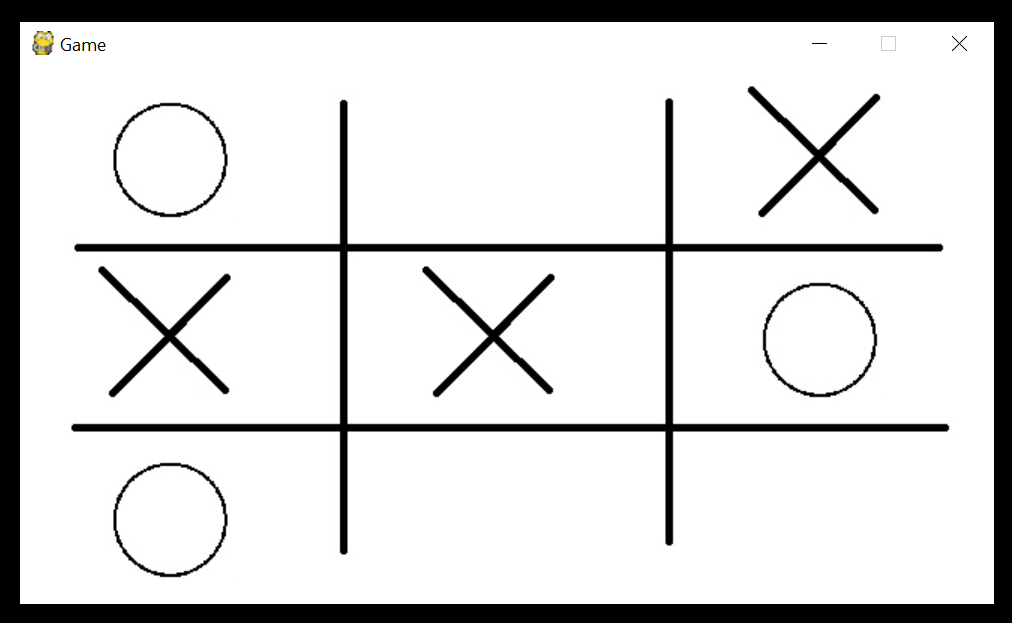

In the Pygame version, the user plays inside an extra window pygame creates. They are presented with the 3x3 board, and click the appropriate location to input their move.

With graphics lovingly crafted in MS paint, the user would be presented with a board layout like this:

Code for the pygame version has been omitted due to complexity, and my desire to target this post towards the algorithm, rather than the UI design process.

Is the game over?

After making the most recent move, we have to check if the next player gets a turn. The game should end when when one player has won (managed to mark 3 locations in a row), or there is a draw (neither player has won, but all locations have been marked).

I’ll check horizontal and vertical by iterating through the rows & columns, then check both the right and left diagonals. If someone has won, I’ll track the winner and how they won (vertical, horizontal, or diagonal).

class TicTacToe():

def is_game_finished(self):

for i in range(3):

# check vertical

if abs(self.board[:,i].sum())==3:

self.winner = self.user

self.how = 'vertical'

return True

# check horizontal

if abs(self.board[i,:].sum())==3:

self.winner = self.user

self.how = 'horizontal'

return True

# check diagonal

if abs((self.board * np.identity(3)).sum())==3 or abs((self.board * np.identity(3)[::-1]).sum())==3:

self.winner = self.user

self.how = 'diagonal'

return True

...

Lastly, if nobody has won, but there are no unfilled locations left, then the game should also end as a draw.

class TicTacToe():

def is_game_finished(self):

...

# is there empty space left?

if ~(self.board==0).max():

self.winner = 0

self.how = 'draw'

return True

else:

# continue the game

return False

Optimal strategy for the AI

Now we have the base game flow built out, except for the opponent logic. Here, I’ll be implementing the perfect strategy as laid out on Wikipedia, which results in a win or draw at worst, by choosing the first available option from the following prioritized list:

- Win: If the player has two in a row, they can place a third to get three in a row.

- Block: If the opponent has two in a row, the player must play the third themselves to block the opponent.

- Fork: Create an opportunity where the player has two ways to win (two non-blocked lines of 2).

- Block the opponent’s fork: Prevent the opponent from achieving two non-blocked lines of 2.

- Center: A player marks the center.

- Opposite corner: If the opponent is in the corner, the player plays the opposite corner.

- Empty corner: The player plays in a corner square.

- Empty side: The player plays in a middle square on any of the 4 sides.

Win or block

Luckily, winning or blocking relies on the same logic - in the former, if the current player has 2 in a row, mark the 3rd, and in the latter, if the other player has 2 in a row, mark the 3rd to block them from winning. Thanks to the choice to represent one player with a 1 and the other with -1, we can use the same logic with an absolute value to identify two in a row.

Much like checking for a winner, we first iterate through the rows & columns, checking for a slice with 2 of the same type and an empty space, then both diagonals, looking for the same. If any slices are found, we fill it with -1, denoting the computer (player O).

The only important thing to note is that we must check every option for a way to win, then, if winning is impossible, check every option to avoid losing. Otherwise, if both players have 2 in a row, the computer might prioritize blocking the opponent from winning, instead of winning itself.

To accomplish this, I have included an extra function that iterates through all lines of 3 and checks for 2 in a row. The first time, that function is called in hopes of winning; the second time, that function is called to block.

class TicTacToe():

def twos(self, direction):

for i in range(3):

# check vertical

if self.board[:,i].sum()==direction*2:

self.board[:,i] = np.where(self.board[:,i]==0, self.user, self.board[:,i])

return True

# check horizontal

elif self.board[i,:].sum()==direction*2:

self.board[i,:] = np.where(self.board[i,:]==0, self.user, self.board[i,:])

return True

# check diagonal

if (self.board * np.identity(3)).sum()==direction*2:

self.board = np.where((np.identity(3)==1) & (self.board==0), self.user, self.board)

return True

elif (self.board * np.identity(3)[::-1]).sum()==direction*2:

self.board = np.where((np.identity(3)[::-1]==1) & (self.board==0), self.user, self.board)

return True

return False

def make_computer_move(self):

# --------------- win ----------------------------

if self.twos(self.user):

return

# --------------- or block ----------------------------

if self.twos(-1*self.user):

return

...

Fork or block fork

A “fork” is an opportunity for one player to create two lines of two at once, thereby winning, as their opponent can only block one line with their turn.

For an example of what this would look like, imagine a game where player X goes first. After 2 turns each, it is once again player X’s turn, and the players have created this layout:

| O | ||

| O | X | |

| X |

On their 3rd turn, player X could mark the bottom right, creating this:

| O | ||

| O | X | |

| X | X |

Now, it is player O’s 3rd turn, but they can only block one of the lines of two - marking either top right, or bottom left - and so player O will lose. Clearly, player O should not have allowed it to get this far, and should have marked the bottom right before player X could do so.

Logically, if the opponent has marked a single position on both of two adjacent sides and no other positions on the sides are marked, the current player should mark the corner between the sides to prevent their opponent from creating a fork. In our example, O should have marked the underlined location:

| O | X | |

| X | _ |

The one exception to this is if the opponent has marked opposite diagonals, like this:

| X | ||

| O | ||

| X |

In this case, marking either the top left corner or bottom right corner would leave the other open, allowing player X to create a fork by marking that location. This “double fork” layout can only be foiled if Player O marks any non-corner location, creating 2-in-a-row, and forcing X onto the defensive on their next turn.

Programatically, we implement this:

class TicTacToe():

def make_computer_move(self):

...

# --------------- block fork ----------------------------

# diagonal double fork

if (self.board!=0).sum()==3 and self.board[1,1]==self.user and ((self.board[np.rot90(self.corner, 2) | np.rot90(self.corner, 0)]==-1*self.user).all()

or (self.board[np.rot90(self.corner, 3) | np.rot90(self.corner, 1)]==-1*self.user).all()):

self.board[1,0] = self.user

return

# single fork

for i in range(4):

if (self.board[np.rot90(self.fork, i)]==self.user*-1).sum()==2 and (self.board[np.rot90(self.fork, i)]==0).sum()==3:

self.board[np.rot90(self.corner, i)] = self.user

return

...

Empty spaces

If the computer couldn’t win, and didn’t have to play defense against 2 in a row or a potential fork this turn, then the computer is going to choose an empty space from the following set of logic:

- If the center is available, mark the center.

- Otherwise, if the opponent has marked a corner and the opposite corner is available, mark that corner.

- If there is no opposite corner available, then mark any empty corner.

- Lastly, mark any empty side.

Performance

I ran Monte Carlo simulations to create a wide variety of random strategies for the user, player X, to see how the computer, player O, would respond. Sure enough, after running 100,000 random games, the computer didn’t lose once, and was able to win 84.7% of the games.

Against a skilled player, the win percentage would be lower, but the objective of simulating so many strategies was to verify that the computer cannot be beaten.

Playing against the AI

PlayCLI.py and PlayPygame.py, both in my UI-examples git repository, allow you to play against the AI (player O), either via the command line or inside of a pygame environment, as many times as you would like.

Code

Complete code can be found in my UI-examples git repository.

This section of the project relies on numpy and pygame.